Introduction

Walk through the bustling ancient medinas of Morocco, and you feel it instantly: a palpable sense of history, tradition, and collective identity. The intricate patterns of zellige tiles, the aromatic spices in the souk, the melodic call to prayer echoing through alleyways, the deeply ingrained hospitality – these are not merely aesthetics; they are threads woven into the very fabric of life, shaping how people think, interact, and perceive the world.1 This is the essence of an accumulated contextual culture: a living, breathing inheritance of history, beliefs, social norms, and shared experiences that profoundly influences every individual within its embrace.

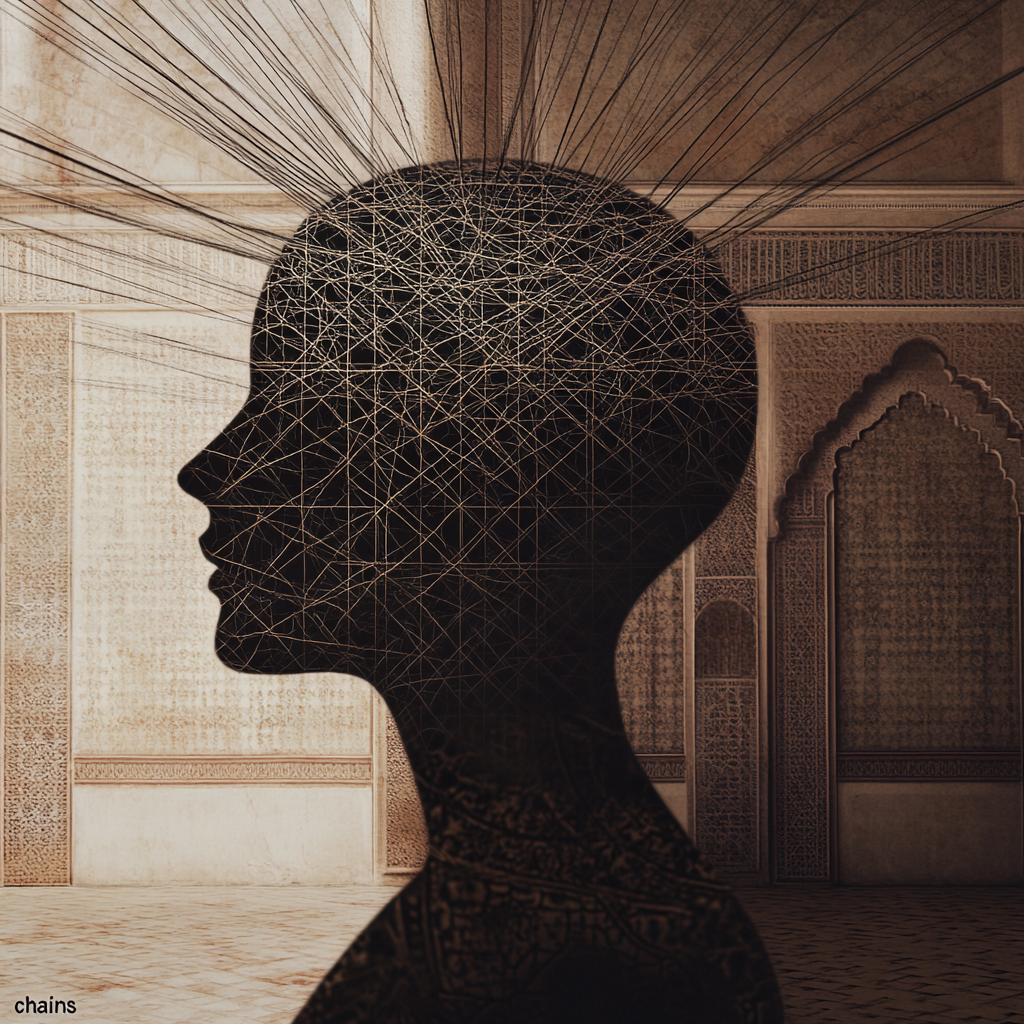

But here lies the provocative and often shocking question: Are we merely beneficiaries of this rich cultural tapestry, or are we, in some profound sense, its victims? Does the very depth of our cultural context, passed down through generations, inadvertently limit our perspectives, stifle our individuality, or perpetuate hidden biases? What is the true impact of this invisible, inherited framework on society?

This article will embark on a critical examination of this complex phenomenon. We will delve into the profound psychological, neurological, and sociological forces through which culture shapes us, often unconsciously. We will expose the startling ways in which this deeply ingrained context can create resistance to change, perpetuate harmful norms, and even dictate our life paths. Relying on scientific reasoning, compelling theories, and diverse cultural insights (with a particular lens on the Moroccan experience), we will peel back the layers to ask: Are we prisoners of our past, or can awareness unlock the key to conscious cultural evolution?

1. The Invisible Architects: How Culture Builds Our Minds (and Our Prisons)

From the moment we draw our first breath, we are immersed in a cultural soup. Language, gestures, rituals, values, and beliefs are absorbed, often unconsciously, shaping the very architecture of our minds.2 This isn’t just about learning; it’s about fundamental programming. Sociologists like Pierre Bourdieu introduced the concept of habitus – a system of dispositions, unconsciously acquired through experience, that guides our perceptions, thoughts, and actions.3 It’s the “feel for the game” of life within a specific cultural context.

This unconscious cultural conditioning is a powerful force. It forms our cognitive schemas – mental frameworks that organize and interpret information – making certain ideas seem natural, right, or even unthinkable.4 For example, the pervasive concept of hshouma (shame or propriety) in Moroccan society profoundly shapes public behavior, dictating everything from appropriate dress to respectful interactions, often without explicit instruction.5 Individuals internalize these norms so deeply that violating them can trigger genuine psychological distress, even if they consciously disagree.

The shocking reality is that this invisible architecture, while providing a necessary framework for social cohesion, can also become an unwitting prison. It can limit our imagination, narrow our perception of possibility, and create inherent biases we aren’t even aware of. We become unwitting products of our past, thinking and acting in ways dictated by a collective history, rather than genuine, autonomous choice. Recognizing this profound, often subconscious, influence is the first step towards breaking free from its unseen binds.

2. The Echo Chamber of Tradition: Resisting the Call for Change

One of the most striking impacts of an accumulated contextual culture is its inherent resistance to change. While tradition provides stability and a sense of continuity, it can also create an echo chamber, where established norms and ways of thinking are constantly reinforced, making it incredibly difficult for new ideas, social reforms, or necessary adaptations to take root.

This resistance is rooted in several psychological and sociological phenomena. Humans exhibit cognitive conservatism, a tendency to maintain existing beliefs and schemas to avoid the discomfort of cognitive dissonance.6 When new information or ideas clash with deeply ingrained cultural narratives, the mind often defaults to rejecting the new in favor of preserving the familiar. Furthermore, the collective memory of a culture, often romanticized or selectively interpreted, can act as a powerful barrier, constantly referencing “how things have always been done.”

The shocking reality is that this adherence to tradition can stall progress and perpetuate systems that no longer serve society. For instance, in many societies rooted in strong historical contexts, including parts of Morocco, efforts to reform certain social laws, update gender roles, or adopt new educational paradigms can face immense popular resistance, not necessarily due to malicious intent, but due to deeply ingrained cultural patterns and a fear of losing a cherished identity. While tradition is a source of strength, its uncritical adherence can turn into a collective stubbornness, sacrificing adaptation for the comfort of the familiar.

3. The Burden of Collective Memory: Carrying History’s Unseen Weight

Cultures are not just collections of current practices; they are living repositories of history. Collective memory, the shared recollections and narratives of a group’s past, profoundly shapes its present identity, societal structures, and intergroup relations.7 The shocking truth is that we often carry the unseen weight of historical burdens and narratives that were forged generations before us, impacting our collective behavior today.

Whether it’s the legacy of colonialism, past glories, periods of oppression, or significant migrations, these historical contexts are transmitted through education, storytelling, monuments, and cultural practices. They influence national identity, shape political discourse, and can even dictate how different communities within a society interact. These narratives, often simplified or mythologized, become part of the accumulated context, influencing biases, aspirations, and fears.

In Morocco, for example, the complex legacy of the protectorate era, the enduring influence of Al-Andalus, the historical resilience of Berber tribes, and the rich tapestry of Islamic heritage all contribute to a unique national identity.8 While this provides a profound sense of rootedness and pride, it can also manifest in subtle biases towards certain foreign influences, an emphasis on historical narratives over contemporary challenges, or an unconscious perpetuation of certain socio-economic structures inherited from past eras. The shocking implication is that we are not just victims of our personal histories, but also of a shared historical past that continues to exert its influence, often unconsciously, on our collective choices and societal trajectory.

4. Identity Foreclosure: When Culture Pre-Determines Your Path

One of the most personal and potentially shocking impacts of an accumulated contextual culture is its tendency towards identity foreclosure. This occurs when an individual adopts a pre-determined identity, career path, or set of values without genuine exploration, primarily to conform to external expectations and cultural norms. Their path is “closed off” before true self-discovery has a chance to flourish.

In cultures with strong familial ties and communal emphasis, such as many found across the Mediterranean and North Africa, including Morocco, societal roles and expectations can be very clear. Children may grow up with implicit or explicit pressure to pursue certain professions (e.g., doctor, engineer), marry within specific familial or tribal lines, or adhere to rigid gender roles. The concept of pursuing a “passion” purely for individual fulfillment might be seen as secondary to contributing to the family’s well-being or upholding its honor.

Psychologically, this can lead to a significant divergence between the “true self” (the authentic desires and inclinations of the individual) and the “false self” (the persona adopted to meet external demands). While it offers the comfort of belonging and avoids social friction, the shocking cost is a stifling of individual potential, a pervasive sense of unfulfillment, and a struggle with identity later in life. Individuals may live lives that are outwardly successful but inwardly hollow, driven by inherited expectations rather than genuine internal compass. Breaking free requires immense courage to challenge deeply ingrained assumptions about who one is “supposed” to be.

5. The Neuro-Cultural Loop: How Culture Wires Our Brains

The impact of accumulated contextual culture is not merely abstract or sociological; it is profoundly physical, literally shaping the very structure and function of our brains. This emerging field of cultural neuroscience reveals a shocking truth: culture isn’t just something we inhabit; it’s something that wires us, influencing our perception, cognition, and emotional responses from the neural level.

Studies have shown that individuals from collectivist cultures (like many in East Asia, or with strong communal ties like in Morocco) tend to show more attention to context and relationships in visual tasks, and their brains might activate different regions when processing self-referential information, often including social context.9 In contrast, individuals from individualistic cultures might show more focus on focal objects. This highlights how cultural practices, social norms, and ways of thinking are deeply embedded in our neural pathways through neuroplasticity.

For example, the emphasis on direct eye contact, personal space, and the importance of non-verbal cues vary significantly across cultures. These culturally defined norms are not just social conventions; they train our brains to process social information in specific ways, influencing everything from empathy to conflict resolution.10 The shocking implication is that our cultural context creates a unique neural filter through which we experience reality, making it inherently challenging to fully comprehend or empathize with perspectives from outside our own cultural matrix. We are, quite literally, hardwired by our heritage, a powerful testament to the “victim” aspect, yet also an invitation to understand and perhaps rewire our own neural maps.

6. The “Us vs. Them” Divide: Tribalism in a Globalized World

One of the most pervasive and shocking impacts of an accumulated contextual culture is its capacity to foster a potent “us vs. them” tribalism. While providing a strong sense of in-group identity and belonging, this deep-seated cultural context can also create rigid boundaries, implicit biases against “outsiders,” and resistance to the diversity and interconnectedness of a globalized world.

Social identity theory explains how individuals derive a sense of self-esteem and belonging from their group affiliations.11 We tend to favor our in-group and view out-groups with suspicion or even hostility. When this is layered with centuries of accumulated historical narratives, stereotypes, and cultural practices, it can manifest as xenophobia, racism, or persistent inter-group conflicts that defy rational explanation.

Despite globalizing forces, deeply entrenched cultural contexts often remain resistant to true integration, leading to cultural clashes and misunderstandings. While Morocco is known for its historical tolerance and coexistence of diverse groups (Berber, Arab, Jewish, European influences), historical narratives can sometimes fuel subtle biases. The shocking reality is that the very comfort and identity derived from our cultural roots can inadvertently create walls, preventing genuine empathy and collaboration with those outside our inherited context. Breaking down these walls requires conscious effort to critically examine our inherited biases and cultivate genuine curiosity about the “other.”

7. The Hidden Curriculum: Implicit Biases and Unspoken Rules

Beyond explicit teachings, every culture transmits a hidden curriculum: a set of unspoken rules, implicit biases, and subtle expectations that shape our behavior and perceptions. This is particularly shocking because these influences operate beneath the level of conscious awareness, making us unwitting perpetuators of societal norms we might otherwise question.

From gender roles to class perceptions, racial stereotypes, and expectations around success or failure, culture instills these biases through subtle cues, media representations, family dynamics, and social interactions. For example, a child might absorb implicit messages about what constitutes “appropriate” work for their gender or social class, even if explicit statements are absent. This influences their aspirations, choices, and interactions throughout life.

Scientific research on implicit bias demonstrates how these unconscious associations can affect our decisions and judgments, even when we consciously strive to be fair.12 In Morocco, subtle social hierarchies or traditional expectations about roles within the family or community can persist through these unspoken rules, influencing opportunities and perceptions.13 The shocking implication is that we are not only shaped by the explicit values of our culture but also by its unwritten codes, which can perpetuate injustice or limit potential without anyone consciously intending it. Uncovering this hidden curriculum is crucial for true societal evolution.

8. The Paradox of Belonging: Security at the Cost of Individuality

Humans have a fundamental need for belonging, for being part of a tribe.14 An accumulated contextual culture offers this in spades: a ready-made community, shared rituals, a sense of identity, and often, a robust social safety net. This provides immense security and comfort. However, this very comfort can come at a profound and often shocking cost: the suppression of individuality and self-expression. This is the paradox of belonging.

The stronger the cultural context, the greater the pressure to conform. Deviating from established norms can lead to social ostracization, judgment, or the feeling of being an “outsider.”15 This can be particularly pronounced in collectivist cultures where the group’s harmony is prioritized over individual desires. While the Moroccan emphasis on family and community provides a strong sense of support and mutual aid, it can also lead to pressure on individuals to choose career paths, spouses, or lifestyles that benefit the family unit rather than fulfilling personal aspirations.

Psychologically, this creates a conflict between the need for relatedness (connection) and the need for autonomy (self-direction), two core human needs. The shocking reality is that many individuals sacrifice their unique expressions, authentic desires, and even their “true self” for the security and comfort of belonging. They become victims of a system that nurtures the collective but can inadvertently stifle the unique spark of the individual. True freedom lies in finding ways to honor one’s roots while also cultivating one’s unique identity.

9. Beyond Determinism: The Power of Cultural Evolution

While the preceding points have highlighted the “victim” aspect of an accumulated contextual culture, the final and most motivational truth is this: we are not merely passive recipients of our cultural inheritance. We are also active agents in its ongoing evolution. Culture is not static; it is a dynamic, living entity that adapts, transforms, and is continuously shaped by the choices and innovations of its members.16

The concept of cultural evolution suggests that cultures, like biological species, adapt over time, often through processes akin to natural selection, where certain ideas, practices, or “memes” (in the sense of cultural units of information) are transmitted and others fade.17 This doesn’t mean a linear progression towards a “better” culture, but rather a constant process of adaptation and change.

The shocking recognition that we are not entirely determined by our cultural context is profoundly liberating. We have the capacity for critical thinking, for challenging norms, for selectively adopting new ideas, and for integrating diverse influences. In contemporary Morocco, for instance, a vibrant youth culture is actively synthesizing tradition with global trends, creating new forms of music, art, fashion, and social discourse that honor heritage while pushing boundaries.18 This active cultural hybridity demonstrates the inherent agency within individuals and communities to shape their future. Our responsibility is not to passively accept our cultural fate, but to engage with it mindfully, celebrating its richness while consciously contributing to its positive, inclusive, and adaptive evolution.

The Awakened Citizen: Shaping Culture, Not Just Being Shaped

The uncomfortable truth is glaring: we are, in many profound ways, products of our accumulated contextual culture. Its invisible architects have built the very frameworks of our minds, its echoes dictate our social dance, and its collective memory colors our perception of the world. The shocking reality is that this inheritance can limit our potential, perpetuate unconscious biases, and stifle the very essence of individual expression. We are, at times, unwitting victims of its powerful, all-encompassing embrace.

But this understanding is not a sentence; it is an awakening. It is the profoundly motivational realization that while culture shapes us, we also possess the inherent capacity to shape culture. We are not merely passive recipients of our heritage; we are its conscious inheritors, its critical evaluators, and its active architects.

To break free from the invisible chains of an unexamined culture requires courage: the courage to question deeply held assumptions, to challenge inherited norms that no longer serve us, to embrace cognitive flexibility, and to cultivate genuine empathy for perspectives outside our own cultural lens. It calls for mindful engagement – celebrating the immense richness, wisdom, and belonging that our culture provides, while simultaneously identifying and challenging its limitations.

By recognizing the power of our inherited context, we gain the agency to make conscious choices: to selectively preserve valuable traditions, to integrate new ideas, to champion inclusivity, and to contribute to a cultural evolution that fosters individual flourishing alongside collective harmony. Be both deeply rooted in your heritage and widely open to the vastness of human experience. In doing so, you transform from a victim of culture into an awakened citizen, actively shaping a more conscious, adaptive, and truly enriched society. The tools for this transformation lie within our awareness and our collective will.